Meniscus

It is a fibrocartilage structure inside the knee joint which articulates between the femoral condyle and tibial plateau.

There are two menisci in the knee – medial and lateral. From the top view, they are semilunar in shape. The medial meniscus looks like the letter “C” and the lateral meniscus, the letter “U”.

Their side profile is triangular or wedge-shaped and 3-5mm thick.

Each meniscus has an anterior horn, body and posterior horn. The medial meniscus is larger than the lateral. However, relative to the size of their corresponding tibial plateau surface area, the medial meniscus covers 50% and the lateral meniscus 75%.

Each meniscus has an anterior horn, body and posterior horn. The medial meniscus is larger than the lateral. However, relative to the size of their corresponding tibial plateau surface area, the medial meniscus covers 50% and the lateral meniscus 75%.

The lateral meniscus is more variable in size, shape and stability.

The menisci articulate with the round femoral condyles and flat tibial plateau.

Meniscus Attachment

The lateral meniscus is more mobile than the medial. Each meniscus is attached to the underlying cartilage and bone at its anterior and posterior roots.

Along its peripheral rim, it is attached to the femoral condyle and tibial plateau by the superior and inferior coronary ligament. The lateral meniscus lacks the coronary ligaments at the popliteal hiatus.

The medial meniscus is also attached to the deep medial collateral ligament (MCL). The posterior horn of the lateral meniscus has the ligaments of Humphrey and Wrisberg connecting it to the medial femoral condyle.

The medial meniscus is also attached to the deep medial collateral ligament (MCL). The posterior horn of the lateral meniscus has the ligaments of Humphrey and Wrisberg connecting it to the medial femoral condyle.

Blood Supply

The menisci are supplied mainly by the superior and inferior branches of the medial and lateral genicular arteries. The middle genicular artery also contributes to their vascularity. Within the capsule, these vessels subdivide to form the perimeniscal capillary plexus. These capillaries penetrate the meniscus to provide its blood supply. In children the whole meniscus is well vascularised but by the age of seven, these vessels recede so that in adult in adulthood, only the peripheral 10-30% is vascularised.

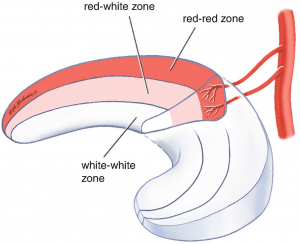

The vascularised peripheral third of the meniscus is known as the red-red zone. The middle third is less vascularised – the red-white zone. The central third is non-vascularised and is named the white-white zone.

The vascularised peripheral third of the meniscus is known as the red-red zone. The middle third is less vascularised – the red-white zone. The central third is non-vascularised and is named the white-white zone.

Meniscus Composition

The meniscus is made of fibrocartilage which is different from the hyaline cartilage that caps the ends of bones. It is well hydrated with 70% being water. Most of the 30% organic material is Type I collagen. Proteoglycans, elastin and cells make up the remainder.

The red-red zone is made up of mostly type I collagen. The white-white has a mixture of type I and type II collagen. Cells in the red-red zone are similar to fibrocartilage. Cells in the white-white zone are similar to hyaline cartilage.

Most of the collagen fibres are organised in a circumferential pattern and some fibres are arranged radially.

Meniscus Function

The meniscus helps with load distribution, shock absorption, joint conformity, stability, proprioception and nutrition of the articulating hyaline cartilage.

Load distribution is most important. During weight bearing activities, there is an axial load of the femur onto the tibia. The wedge shape structure and circumferential orientation of its collagen fibres allow the meniscus to convert this axial load to a sideway force, thereby dissipating the stress on the knee cartilage. Numerous studies have shown that removal of meniscal tissues will increase the stresses on the articulating cartilage. This will in turn lead to articulating cartilage wear, known as osteoarthritis.

Mechanism of Injury

Traumatic tears in young patients usually occur as a result of twisting the knee while the foot is planted on the ground. It often happens during sporting activities.

In higher energy injuries, meniscal tears can occur in association with other pathologies such as fractures and torn ligaments.

Degenerative tears occur in middle-aged or older patients. There is usually no recorded injury. They occur overtime and is due to the wear and tear process. These patients often have mild to moderate osteoarthritis.

Symptoms & Signs

Patients mostly experience pain localised to the site of the tear. It is aggravated by weight bearing or pivoting activities. Patients may also have mechanical symptoms such as painful clicking or catching.

Some patients with displaced tears cannot fully extend their knee as the torn fragment is jammed between the femoral condyle and tibial plateau. This is known as locking.

Patients can walk with a limp due to pain or an inability to fully extend the knee. An effusion can be detected. There is localised tenderness with palpation at the tear site.

Special provocative test such as the McMurray test can cause pain.

Types of Tears

Tears can be described by their configuration.

Commonly seen tears are horizontal, vertical or radial. Complex tears are a combination these types.

Bucket handle tears are extensive vertical tears where the torn fragment can be displaced. This movement of the torn fragment is similar to that of a handle of a bucket; moving from one side to the other.

Tears can also be described by their location – posterior horn, body or anterior horn. Most tears occur in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus.

Meniscal tears are also classified according to their zone of vascularity. Tears can be located in the red-red, red-white or white-white zone. Tears in the red-red zone are more vascularised and have a better chance of healing following repairs.

Investigations

MRI is the best tool to assess meniscal tears. When MRI scans cannot be performed then consider CT arthrograms where a contrast solution is injected into the knee joint. Standard CT scans and ultrasound are not helpful in studying meniscal tears.

Management

Meniscal tears are either left alone, repaired or resected (meniscectomy).

Displaced bucket handle tears need urgent surgery to unlock the knee and prevent further damage to the torn meniscal fragment as well as the adjacent cartilage. The goal is to repair these tears whenever possible. Unfortunately, when the tear is chronic, it becomes irreducible or macerated. In these situations, the torn fragment has to be resected.

Repairs are performed on almost all traumatic tears in children and young adults. Most repairs are performed arthroscopically. Sometimes, an open incision is made to help protect the neurovascular structures and to assist with the repair.

Knee surgeons have several different techniques and special instruments to repair torn menisci. Repair techniques broadly fall into 3 groups: inside-out, outside-in and all inside. Decision on which technique to use depends on the location of the meniscus and surgeon’s preference.

Due to the poor blood supply of the meniscus, not all repairs will heal. To increase the chance of healing, surgeons freshen up the torn edges (abrasion), create blood channels to the capsule (trephination), bring in bone marrow stem cells (notch microfracture) and insert a blood clot to the repair site.

Due to the poor blood supply of the meniscus, not all repairs will heal. To increase the chance of healing, surgeons freshen up the torn edges (abrasion), create blood channels to the capsule (trephination), bring in bone marrow stem cells (notch microfracture) and insert a blood clot to the repair site.

When repairs are not possible, the torn fragment is removed. This is termed meniscectomy.

Surgery on degenerative tears in knees with pre-existing osteoarthritis do not improve pain. Degenerative tears are not repaired as they do not heal. The damaged part of the meniscus is removed to relieve mechanical symptoms such as painful clicking or locking.

In meniscectomy, the goal is to minimise the amount of meniscal tissue removed. Research have shown that larger meniscectomies will lead to increase in cartilage stresses and eventually osteoarthritis.