Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Children (information for Health Providers)

Dr. Quang Dao

Introduction

Intra-substance tears of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in children were rarely reported in the past. Historically, most ACL injuries involved an avulsion of the tibialeminence at the site of the tibial ACL insertion.

However , mid-substance ACL injuries in children and adolescents are becoming more common. This is due to increased participation in competitive sports at a much younger age, combined with the higher pressure placed on these young athletes to excel. With better knowledge of the condition and improved diagnostic tools, clinicians are now more accurately diagnosing this injury.

Traditionally, paediatric ACL injuries have been managed non-operatively due to the fear of damage to the open physis (growth plate). However, with improved technical understanding, more reconstructive surgeries have been performed to prevent further meniscal and chondral damage.

Anatomy

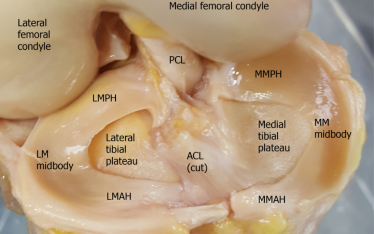

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is a band of dense connective tissue connecting the distal femur and proximal tibia. It is like a rope or ribbon with one end attached to the medial surface of the lateral femoral condyle and the other end, to the central part of the tibial plateau. It is one of the main stabilisers of the knee. It prevents anterior translation of the tibia on the femur. It also provides rotational stability of the knee.

MFC – medial femoral condyle

LFC – lateral femoral condyle

AM – anteromedial bundle of the ACL

PL – posterolateral bundle of the ACL

The ACL is composed of 2 bundles, the anteromedial bundle (AMB) and the posterolateralbundle (PLB). They are named according to their insertion points into the tibia. Histologically, there is a vascularized fibrous septum that separates the two bundles.

Histology examination demonstrates a septum (black arrows) dividing the anteromedial (AM) and posterlateral (PL) bundle

The 2 bundles are present at 16 weeks of gestation. The AMB is tighter in flexion and the PLB is tighter in extension. The AMB is more important in anterior translation while the PLB is more important in rotational stability. The distance from the femoral origin to the femoral physis remains consistent from gestation to maturity and averages about 3 mm.

The femoral intercondylar notch continues to develop throughout skeletal maturity. However at age eleven years, the width of the anterior notch ceased to increase in size. The male notch is usually larger by this age.

ACL in a fetus with anteromedial (AM) and posterolateral (PL) bundles

Epidemiology

There is still lack of proper demographic data to reflect true rates of ACL injuries. However, there are a few small studies which convincingly demonstrate a rapid rise in the treatment of these injuries. Paediatric ACL injuries now form approximately 3% of all ACL injuries. Dodwell et al used a billing and discharge database in New York State from 1990 to 2009, to show an increase in the rate of ACL reconstructions in patients aged 3 to 20 years from 17.6 to 50.9 per 100,000 population. They also showed the highest rate was in patients aged 17 years. Souryal and Freeman reported an annual incidence rate of 16 per 1000 for ACL tears in a cohort of high school athletes. Stracciolini et al. found that 9.4% of presentations to the Division of Sports Medicine of a large, academic paediatric medical centre were ACL tears.

Risk Factors For ACL Injuries

Injury risk factors are either intrinsic or extrinsic. The intrinsic factors are inherent to the patient such as age, gender, hormonal differences, mechanical alignment, anatomic variation of the ligament and femoral notch, previous reconstruction and ligamentous laxity. The patient’s playing style, skills, preparation and ability are all intrinsic factors. They have a significant bearing on the risk of ACL tears.

ACL injuries are more common in boys due to the higher number of boys participating in at risk sports. However, girls have a higher relative risk per athlete of sustaining ACL tears. Some of the proposed factors for this difference include sex hormone receptors located on the ACL, excessive femoral anteversion, increased Q-angle, decreased intercondylar notch width, smaller ACL size relative weakness in core strength, higher quadriceps to hamstrings ratio and deficient neuromuscular control.

Extrinsic risk factors are those extrinsic to the patient. The most important of these is the type of sports they play. High risk sports include soccer, netball, football, basketball and skiing. Other factors include hard and dry playing surfaces such as synthetic surfaces with high friction. Boots with higher number of studs (cleats) also pose increased risk. Increased number of cleats provide more traction with the ground but can cause the foot to be stuck while the remainder of the body is twisted on the knee. Using the right type of shoe for different surfaces can help reduce the risk of injury.

Studs of one of the most popular soccer boots

Injury Patterns

Injuries to the ACL can occur as a bony avulsion, mid-substance tear, complete, partial, in isolation or associated with other injuries.

Avulsion injuries tend to occur in younger patients. Most avulsions are at the tibialinsertion, rarely are they found on the femoral side. Kellenberger found that in a group of 63 skeletally immature patients with ACL injuries, 80% of those less than 12 years of age involved tibial eminence fracture, while 90% of those over 12 years of age had intrasubstance tears. Staninitski et al found in a review of 70 patients aged 7-18 years old, the rate of tibial spine fractures was three times more common in those aged 7-12 years when compared to those 13-18 years of age. Detectable laxity on clinical examination after healed avulsion injuries suggest that there was intra-substance stretch of the ligament at the time of the avulsion. Undisplaced Type I injuries can be managed conservatively in a cast or brace. Displaced avulsions Type II and III are managed with reattachment of the fragment and fixed with sutures, wires or screws.

Midsubstance tears can be complete or partial. The partial tears tend to affect either the anteromedial or posterolateral bundle. Patients with partial tears can still be managed conservatively if their knees remain stable.

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) views showing a Type III tibial eminence fracture.

Presentation

The presentation of ACL tears in children is similar to that in adults. It usually resultsfrom an indirect sporting injury. The player suddenly changes direction causing a pivoting load on the knee. Abrupt deceleration or off-balance landing from a jump can also tear the ACL. Usually the player feels a “popping” or tearing sensation in the knee. The knee gives way and the player falls to the ground. There is immediate severe pain. Swelling is usually not seen until several hours later. Stanitski et al. found 47% of the preadolescent group and 55% of the adolescents with acute haemarthrosishad partial or complete ACL tears. It can be painful to weight bear for the first 2 weeks. Significant pain suggests other associated injuries such as torn menisci, osteochondral fracture or injuries to other ligaments.

Swollen right knee due to a large haemarthrosis

Initially, the knee will be swollen with restricted motion. Special tests such as anterior drawer, Lachman, and pivot shift can be positive.

Tap on image to play video. Lachmann and Pivot Shift tests.

Investigation

X-rays can show a tibial eminence avulsion or a Segond fracture.

MRI is the best tool to diagnose a ruptured ACL and to detect associated injuries.

Management Controversies

MRI showing normal ACL MRI showing ruptured ACL

The management of ACL injuries in the children can be controversial. There are differing views of what to do and when to do it.

Concerns with reconstructing

Traditionally, ACL injuries in children were treated with activity avoidance, bracing and delaying reconstructive surgery. The main reason for this approach is the concern of causing a growth disturbance in the operated leg of these skeletally immature patients. Surgery in these patients was usually delayed until their growth plates have fused. This is approximately 14 years for girls and 16 years for boys.

When growth arrest occurs it usually causes shortening, lengthening or angular deformity. The posterolateral position of the femoral tunnel or the over-the-top groove is very close to the femoral physis and can cause either valgus or flexion deformity of the distal femur. Injury to the anterior tibial physis can result in recurvatum of the knee.

Full length radiograph showing an increased valgus right knee following physeal sparing ACL reconstruction using ITB

The evidence for physeal injury in ACL reconstructions mainly come through animal studies, case reports or surgeons’ questionnaires.

Previous animal experiments have shown that the risks to growth arrests are higherwhen the physeal defect is greater than 7-9% of the total physeal area. Pananwala et al. showed in their MRI study of 39 knees in patients aged between 11 and 16 yearsthat a 9mm drill of the proximal tibia only created a 2.76% defect in the proximal tibia. Some researchers also showed that placing a soft tissue graft across the physealtunnel in the rabbit model was protective from causing an arrest. It has been shown by Edwards et al. that placing an overtensioned fascia lata graft in the canine model can cause valgus femoral and varus tibial deformities without having radiological or histological evidence of physeal bar formation.

In a survey of the Herodicus Society (an international sports medicine society) and the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Study Group, 15 of 140 respondents reported a growth disturbance following ACL reconstructions in skeletally immature patients. Of these 15 cases, 12 were on the femoral side and 3 were on the tibial side. Angular deformities consisted of 10 distal femoral valgus and 3 tibial recurvatum. Of the 2 cases with leg length discrepancy, one was 2.5 cm short and the other was 3 cm long. Most of these growth disturbance can be explained by surgical error such as placing a staple or suture across the physis, using the patellar tendon as graft with the bone plug across the physis, drilling a very large tunnel of 12mm and using extraarticular lateral tenodesis.

Koman reported a valgus deformity following ACL reconstruction using bone-patellar tendon-bone graft with femoral fixation hardware placed across the lateral femoral physis. This valgus deformity required a corrective osteotomy.

Concerns with not reconstructing

The problem with not reconstructing these ACL deficient knees is they often result in recurrent knee instability, meniscal and chondral damage as well as sports related instability. These younger patients are usually non-compliant with activity modification and brace wearing. Away from organized sports, they still perform running and pivoting maneuvers especially during breaks at school.

Millet found that medial meniscal tears were more common (36% versus 11%) in those patients who underwent reconstruction beyond 6 weeks from the time of injury compared to those who had surgery within 6 weeks. Graf studied 8 patients (average age 14.5 years) who underwent conservative management for ACL tears and found that 7 patients developed new meniscal tears at an average of 15 months following their injuries. Lawrence et al. reviewed 70 patients with average age 12.9 years and showed that there was an increased rate of meniscal tear and high grade chondraldefects (Outerbridge grades II to IV) if time from injury to surgery was delayed for more than 12 weeks. They also showed that rates of irreparable meniscal repairs were three times more frequent (24% vs. 7%). McCarroll et al reported 37 of 38 adolescent patients, at mean follow-up of 29 months, had recurrent instability. New symptomatic meniscal tears were observed in 27 patients. Only 16 attempted to return to sports, but all experienced instability. Kannus et al. observed good to excellent results in patients with partial, grade II tears who were managed non-surgically for 8 years. However, they reported poor results with chronic instability and arthritis in the complete grade III tears. Angel and Hall reported the majority of their 27 patients had pain and activity limitations. At average follow-up of 51 months, 4 patients had arthroscopic surgery, 4 had ACL reconstructions and another 3 had reconstruction recommended.Kocher and co-authors reported that up to one third of patients (mean age 13.7 years) with a partial ACL tear who were managed in a hinged knee brace and appropriate rehabilitation still eventually requires reconstruction for instability. They recommended surgery for patients with greater that 50% tears, tear of the posterolateral bundle and grade 2 pivot shift test.

There are also laboratory and clinical evidence that demonstrate delays in surgery cancause clinical instability and damage to the menisci and cartilage. Most paediatricknee surgeons these days tend to recommend early reconstruction to their patients.They utilize various techniques to minimize the risk of growth disturbance.

Tear of the posterior horn medial meniscus following a neglected ACL rupture

Assessing Patient’s Age

The patient’s age is one of several important factors in determining timing of the surgery. A patient’s chronologic age (based on their birthdate) does not always correlate with their development. In a classroom with students of the same age, there is wide spectrum of height and physiologic maturity.

Children of the same age can develop at different rates and resulting in different heights

There are several ways to determine how old a patient is and when to expect their growth to cease.

X-ray of the left hand is used to predict bone age

Tanner staging

Surgical Options

There are various methods to reconstruct the ACL in a skeletally immature patient. The most appropriate method is dependent on the patient’s age and physiologic maturity. The goal is to anatomically reconstruct the ligament without compromising growth. The surgical options include transphyseal, physeal sparing and hybrid techniques.

Transphyseal techniques involve drilling through one or both the tibial and femoral physis. Physeal sparing techniques include drilling tunnels only in the epiphysis or without drilling any tunnels by passing the graft in the over-the-top position of the femur and under the anterior intermeniscal ligament of the tiba.

Combined intra-articular and extra-articular reconstruction using iliotibal band (modified MacIntosh) technique

Micheli et al. described a modification of the MacIntosh and Darby technique. The iliotibal band is harvested via a single or double lateral incision technique. Approximately 15-20cm of the band is required depending on the patient’s size. It is detached proximally and left attached to Gerdy’s tubercle distally. The graft is tubularised with nonabsorbable sutures. The ruptured ACL remnant is minimally debrided and utmost care is taken to avoid damage to the perichondral ring around the posterior aspect lateral femoral condyle. Using a curved clamp, the graft is passed around the lateral femoral condyle, over-the top position and into the joint. Proximally the graft is fixed to the lateral femoral condyle by sutures at the insertion of the lateral intermuscular septum. This is performed with the knee at 90 degrees and neutral rotation. The graft is then passed under the intermeniscal ligament at the front of the tibia, into a rasped trough of the tibial epiphysis and attach to the proximal tibia via an elevated periosteal sleeve. Additional fixation to the proximal tibia can be achieved by a post, staple or suture anchor.

Kocher et al. reported on 44 patients who underwent reconstructive surgery using this technique. There were two ruptures occurring at 4.7 and 8.3 years postoperatively. No growth disturbance was identified. The International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score was 96.7 and Lysholm score was 95.7.

Although this technique does not reproduce an anatomic ACL, it has been shown by Kennedy et al. that in a cadaveric model it most closely restore the native ACL kinematics when compared to the all-epiphyseal or transtibial over-the-top reconstruction.

Transepiphyseal anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

In 2003, Anderson described a technique where the tunnels are placed entirely within the femoral and tibialepiphysis, without crossing the physis. The principle behind this technique is to achieve anatomical reconstruction of the ACL without compromising the physis.

This procedure uses fluoroscopy to ensure that drilling remains in the epiphysis. Both gracilis and semitendinosus tendons are harvested and doubled to form the graft. The graft is passed through the epiphyseal tunnels and fixed on the femoral side using an Endobutton and washer. It is fixed to the proximal tibia using a screw post.

Transphyseal anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

This technique is very similar to the one used in adult ACL reconstruction. Its principle is to anatomically reconstruct the ruptured ACL by drilling tunnels through the physis and entering the joint at the injured ACL footprints. There are a few special considerations to minimize the risk of growth arrest. They include

Hybrid transphyseal anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

During a hybrid reconstruction, only one of the tunnels crosses the physis. Usually the graft is passed in the over-the-top position in the femur. The tibial tunnel is drilled across the physis. The theory behind this approach is that the proximal tibial physisgrows at a slower rate than the distal femoral physis. So if there was a growth disturbance it will only be small. The other thought is the tibial tunnel is more central and any deformity is more related to leg length rather than angular deformity and thus easier to manage with nonsurgical means such as a shoe lift if the deformity is small.