Patellar Dislocation

Patellar dislocation occurs when there is total loss of contact between the patellar and the femoral groove.

Patellar subluxation is defined as partial loss of contact between the patellar and femoral groove.

Both these disorders belong to the spectrum known as patellofemoral instability (PFI). The incidence of PFI in children and adolescents is 43 per 100 000. It is most common in the age group 10-14 years old.

Almost all patellar dislocations and subluxations are lateral and most reduce spontaneously.

Photograph showing lateral dislocation of the left patella

Radiograph showing a laterally subluxed and tilted patella. There is a small fracture of the patella.

Radiograph showing a lateral dislocation of the patella. There is a small avulsion fracture of the medial patella

Pathomechanics

Patellar stability relies on three factors

- Static

- Size, contour and height of the patella & femoral trochlea

- Varus & valgus alignment of the lower limb

- Bony rotation

- Passive

- Ligament (medial patellofemoral ligament)

- Joint capsule & retinaculum

- Iliotibial band

- Dynamic

- Muscle (vastus medialis obliquus)

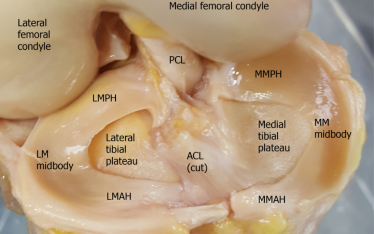

As the knee reaches full extension, the patella tracks slightly superior and lateral to the trochlea. During early flexion (0-30 degrees) the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) guides the patella into the trochlea. It is the most important medial restraint in early flexion. Beyond 30 degrees, the bony anatomy of both patella and trochlea is the main stabiliser. Past 90 degrees, the patella engages into the notch.

The vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) is the most important dynamic stabiliser of the patella. It acts throughout the range of motion but plays more a significant role beyond 60 degrees of flexion when its fibres run perpendicular to the line patellar tracking.

Mechanism of Injury

Patellar instability can result from traumatic or non-traumatic events.

During traumatic dislocations the force can be direct or indirect. With direct mechanisms, the patella experiences a laterally directed force causing it to dislocate laterally. It can also result from a medially directed force on femorotibial joint of the knee, causing the knee into valgus and leaving the patella behind in the dislocated position. This type of direct injury usually occurs during a football tackle.

Indirect injuries result from a twisting knee when the foot is planted on the ground and the rest of the body changes direction. Most indirect injuries causing patellar dislocations occur in cutting and pivoting sports such as soccer, football, basketball and skiing.

Non-traumatic dislocations tend to occur with activities of daily living, requiring minimal force and often reduce spontaneously. These patients also report recurrent subluxations between episodes of true dislocations.

Risk Factors

There are several major risk factors for patellar dislocations. They can be classified as general or limb specific factors.

The general factors are

- Sports which involve pivoting and cutting manoeuvres such as soccer, football, basketball, netball and skiing.

- Previous patellar dislocation

- 20-30% after first time dislocation

- Rate is higher when the physis is still open

- Rate is 0% if patient is older than 40 years

- Family history

- Female

- Unclear if female sex is a risk factor as there are conflicting evidence

- Ligamentous laxity

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Marfan syndrome

- Down syndrome

The limb specific risk factors can be subdivided into static, passive and dynamic. It can be further stratified into above, at and below the patella.

- Static

- Genu valgum

- Excessive internal femoral torsion

- Excessive external tibial torsion

- Increased Q angle

- Patella and trochlea dysplasia

- Patella alta

- Passive

- Ruptured or stretched MPFL

- Tight lateral retinaculum

- Tight iliotibial band

- Dynamic

- Weak VMO

Classification

There are several classification systems but the following is most popular.

- Single

- Patients present for the first time with a dislocation.

- Usually traumatic

- Recurrent

- This is the second or subsequent dislocation

- Can be traumatic or non-traumatic

- Habitual or Obligatory

- The patella dislocates with each cycle of knee motion

- Usually dislocates when the knee is flexed and reduces when the knee extends. The reverse can also occur.

- Permanent

- Congenital

- Acquired following infection or surgery

Video clip showing habitual dislocation

Closed Reduction

Most dislocations are lateral and reduce spontaneously. However some will require a closed reduction.

Following a patellar dislocation, the knee is usually held flexed. Due to the lateral & posterior position of the dislocated patella, the extensor mechanism of the knee now becomes a knee flexor. Pain and spasm of the thigh muscles, namely the hamstrings and quadriceps keep the knee in the flexed position.

The most important part of the reduction procedure is to relax the patient in a supine position. Slowly extend the knee. Only push and guide the patella back into place once the knee is fully extended. This should require minimal force. Forcing the patella to reduce while the knee is still flexed can cause osteochondral injuries to either the patella or lateral femoral condyle.

Once the patella is reduced, immobolise the knee in extension either with a brace or cast. Immobilastion is limited to a maximum of two weeks. Longer periods will cause stiffness, weakness and dysfunction of the dynamic stabiliser of the patellofemoral joint. Radiographs are performed to confirm reduction and to exclude any fracture.

Clinical Examination

Following an acute traumatic dislocation the knee is assessed to ensure that the patella is reduced. A large effusion or significant pain and tenderness should raise suspicion of a fracture and will require further investigation. The knee might be too painful to allow for a thorough examination. But when possible assess for ligamentous and meniscal pathologies.

Once the pain and swelling have settled, a comprehensive examination is carried out to detect the risk factors for patellar instability as well as excluding other injuries.

Important signs to look out for are

- Genu valgum

- Genu valgum increases the risk of patellar instability

- Knee hyperextension and planovalgus feet suggesting ligamentous laxity

- Squinting patella

- Reflects excessive internal femoral rotation

- In-toeing gait

- Reflects excessive internal femoral rotation

- J-tracking of patella

- Abrupt lateralisation of the patella in terminal knee extension

- Patellofemoral crepitations

- Can be due to chondral damage in the patellofemoral cartilage

- Quadriceps weakness

- Focus on VMO size and activation

- Effusion

- Indicates recent instability or osteochondral injury

- Patellar tilt

- Normally the patella should be able to be tilted horizontally

- Inability to horizontalise the patella indicates tight lateral retinaculum

- Patellar translation

- In extension the patella should be translated 1-2 quadrants medially or laterally

- Q angle

- Upper limit is 10 degrees in males & 15 degrees in females

- Rotational profile

- Assess for excessive femoral anteversion (internal torsion) and external tibial torsion

- Ligamentous laxity

- At least 3 of 5 Wynn-Davies criteria

- Passively touching the thumb to the forearm with wrist flexed

- Fingers parallel to forearm with passive wrist extension

- Elbow hyperextension

- Knee hyperextension

- Passive ankle dorsiflexion greater than 45 degrees

- At least 6 of 9 Beighton Hypermobility Score

Investigation

Radiographs are performed initially to ensure that the patella has been reduced and to exclude any fracture. Due to pain in the acute period following a dislocation, it may be possible just to get the anteroposterior (AP) and lateral images. Once pain and swelling have settled, a skyline view is important to detect any fracture, assess patellar position, tilt as well as trochlear dysplasia.

AP X-ray showing a lateral patellar dislocation

Skyline x-ray showing a fracture of the patellar apex following a dislocation

Photograph of a patellar osteochondral fracture

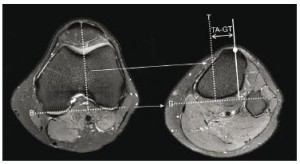

CT scans are good for detecting fractures. They can also be used to calculate the tibial tuberosity – trochlear groove distance (TT-TG). The normal value is 13mm. A TT-TG of 20mm is pathological and indicates that tibial tubercle transfer should be part of the surgical plan.

Calculating TT-TG Distance

Axial CT image through the most prominent part of the tibial tubercle is superimposed on the image of the deepest part of the trochlea. Line 1 joins the posterior femoral condyles. Line 2 runs perpendicular to line 1 and through the trochlea. Line 3 is perpendicular to line 1 and through the centre of the tubercle. TT-TG is the perpendicular distance between line 2 & line 3.

TT-TG distance can also be calculated on MRI scans. The normal value is 10mm.

Patellar height measurement

Patella alta (high riding patella) is a risk factor for patellar instability. There are several methods to measure patellar height.

Insall-Salvati Ratio

The lateral radiograph is taken with the knee flexed at 30 degrees.

Two lengths are required to calculate the ratio.

- TL = tendon length (red) which is the distance from the inferior pole of the patella to the point of insertion at the tibial tuberosity

- PL = patellar length (yellow) which is the distance from superior to inferior pole of patella

Insall-Salvati ratio = TL (red)/ PL (yellow)

A normal value = 0.8 -1.2

Patellar alta > 1.2

Patella baja <0.8

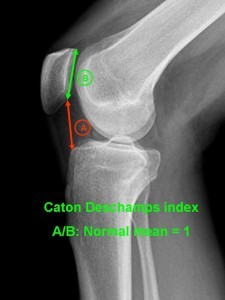

Caton Deschamps index (CDI) requires two measurements.

- A = distance from patellar inferior articulating edge to top of tibial plateau

- B = length of patellar articulating surface

CDI = A/B

Normal = 0.8 – 1.2

Patella alta > 1.2

Patella baja < 0.8

Blackburn-Peel Index (BPI)

A horizontal line is drawn along the tibial plateau.

Perpendicular to this line, the distance is measured to the inferior aspect of the patellar articulating cartilage (1).

A second measurement is made along the patellar articulating surface (2).

BPI = (1) / (2)

Normal value = 0.8 – 1.0

Patella alta > 1.0

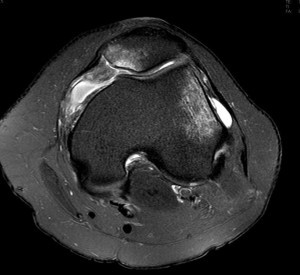

These days MRI scans are performed routinely in many centres for all patellar dislocations. It should at least be performed for those cases associated with a high energy trauma, persistent pain, swelling or fractures identified on radiographs. MRI scans have the ability to detect chondral injuries, tears of the MPFL, calculate the TT-TG distance and exclude other internal derangements such as meniscal tears or ligamentous ruptures.

Common MRI findings following a traumatic patellar dislocation include

- Haemarthrosis

- Bony contusions or osteochondral fractures involving the medial patellar facet and lateral femoral condyle

- Rupture of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL)

Features on MRI scans which are risk factors for patellar dislocation

- Dysplastic femoral groove

- Dysplastic patella

- Patella alta

- Subluxed patella

- Laterally tilted patella

- Deficient vastus medialis obliquus (VMO)

Axial MRI scans demonstrating an effusion, bony contusions of the medial patella and lateral femoral condyle, rupture of the MPFL from its femoral insertion.

Coronal MRI showing bony contusion of the lateral femoral condyle